Topgun Principle: If You Leave An Engagement, Don’t Go Back In

Written by Dave “Bio” Baranek

One of the principles Topgun taught us was that if you leave an engagement, you should not go back in. There were examples from combat (and other Topgun classes) of fighters becoming engaged and bugging out, and then re-engaging with bad results, such as being shot down.

On a 4vUNK hop (4 F-14s versus an UNKnown number of adversaries) in Week Five, flying over the Pacific, we were in a large furball.

There must have been nine or ten aircraft within about five miles, a sphere of airspace in which they could influence each other. Some bogeys had already been killed.

After Jaws and I took several shots we decided we should leave, so we coordinated with our wingman Boomer and called, “Jaws bugging north.”

The answer was, “Boomer bugging west.” Good.

Jaws pushed the nose forward to descend and went to Zone 5 burner.

My job was now defensive lookout, so I focused 90 percent of my attention behind us, watching the swirling black dots recede as we rapidly accelerated through Mach 1.

I told Jaws it seemed like a clean bug, and when I looked forward I saw the amazing spectacle of a shock wave sliding backwards on the Plexiglas canopy. It looked like a plate of glass that conformed to the shape of the canopy and moved aft as our speed increased.

We hit Mach 1.3 (more than 800 knots) easily and were still accelerating.

When I said it was a good bug Jaws pulled the throttles back from Zone 5 and the shock wave rapidly slid forward and disappeared as we slowed below Mach 1.

“Feel like poking our nose back in?” he asked.

“Sure!”

Jaws executed a max-performance left turn while I slewed the radar to its limits and set it for manual operation at short range.

In the turn I saw black dots on my green scope. The small ones were A-4s or F-5s, the larger ones were F-14s still engaged.

On the ICS I told Jaws I had contacts at nine miles and said, “Steady one-nine-zero.”

Squeezing the trigger on my hand controller, I took a lock.

The symbology on Jaws’s head-up display changed and the diamond showed the radar target. Although I tried to be selective, he said, “That’s an F-14,” so I went back to search mode, looked for a smaller blip, and took another lock.

The second lock led Jaws to make a radio call of, “Belly Fox One, A-4 chasing the F-14 at 13,000 feet.”

The A-4 immediately performed a roll to acknowledge that he was dead. We had shot at his belly, so he had no way to see the shot and no chance to defeat it.

Over the ICS Jaws said, “Let’s not press our luck.”

We rolled into another max-performance turn, once again away from the furball.

Over the radio I said, “Jaws bugging north.” We joined up with Boomer and returned to Miramar.

Since we were not on the TACTS Range, the debrief would rely on reconstructing the intercepts and engagements from memory and notes, and our cockpit tape recorders.

After landing we taxied our jet through Miramar’s hot refueling pits, where a sailor attached a thick hose and refueled the plane.

Refueling took ten to fifteen minutes (it only seemed like longer), and while waiting one of us would play our mini tape recorder over the ICS.

We listened, made notes, and refreshed our recollection of the flight. We rarely stopped on a specific point on the tape since we agreed to play all runs through before focusing on any incidents.

I’m sure most fighters listened to their tapes in the pits. If not, they should have. It clarified recollections and filled in gaps in my notes, helping me to come up with a fairly complete and accurate picture of the flight.

After my lesson in the 1v1 debrief I wanted to be ready at any time to debrief a portion of the flight or explain what our jet was doing and why, and the mini tape recorder helped me prepare.

Our return to take a missile shot was mentioned in the debrief, thanks to a bogey who had been killed and saw the whole thing as he cruised above the action.

Since we had made it work, the instructor lead stated the obvious (“Don’t do this”) but didn’t make a big deal about it.

Additional Notes:

The shock wave that I saw was well-defined and transparent; the “plate of glass” description is the best I can think of.

It was not the nebulous cloud-like “vapor cone” that is sometimes photographed, although that can look spectacular. (I’ve seen that, too – from the inside.)

The vapor cone forms at transonic speed, approximately 0.9 Mach, when moisture in the atmosphere condenses.

The shock wave in the story was created above 1.0 Mach and moved aft as we passed through 1.3 Mach, which is quite a bit faster than the transonic vapor cone.

I found a photo online showing similar shock waves created by a Blue Angels F/A-18 Hornet at transonic speed. I’ve added yellow arrows that point to the shock waves.

If you would like to see more explanation, search the Internet for “aircraft shock wave photo” – with shock wave as two words.

UPDATE: Several people questioned why this article was about a principle learned and taught at TopGun which Bio & Jaws then didn’t follow, so here’s his comment on that:

When I wrote this piece, I was really thinking about (1) the shockwave on the canopy, one of the most amazing things I’ve seen in my life, and (2) how we played our tapes back in the fuel pits to prep for the debrief.

As I recall, the reason Topgun recommended not re-entering a fight can be summarized in a graph that showed kill ratio went down as time in an engagement increased.

Of course there was a climb for the first 45 sec to 1 minute, but there was a point of diminishing returns. As noted, this was based on actual combat and reinforced by Topgun class engagements.

And there are circumstances where “rules” can be broken. But in general, it was a good idea to continue a bugout once you made the decision and started to leave.

We were near the end of the Topgun class and I guess we felt a little cocky. It worked out for us that day.

Thanks for reading the article I hope this answers your question.

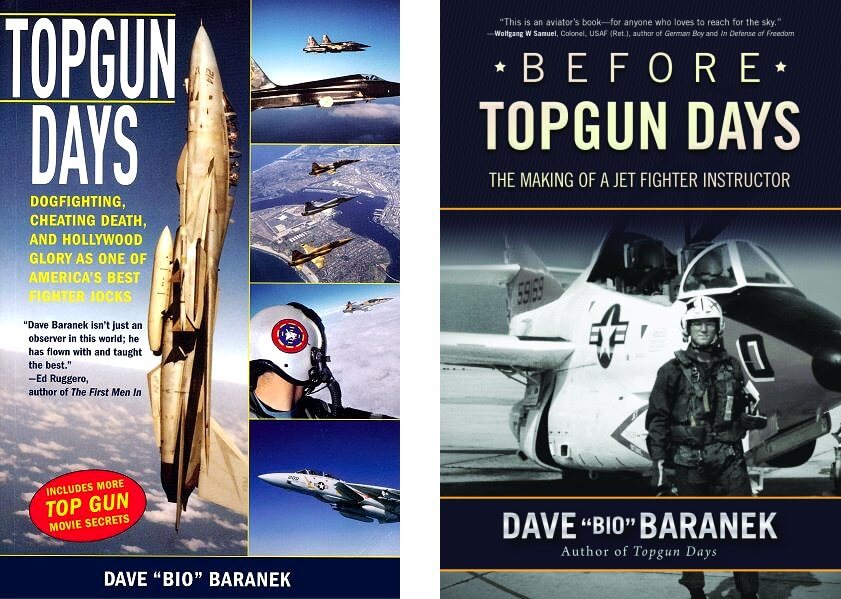

The above article was taken from Dave “Bio” Baranek’s TopGun Days book, which you can learn more about here: TOPGUN DAYS

Follow Bio

To be alerted about Bio’s new articles, videos, books and other military aviation related content, just enter your name & email address into the form below and click the button.

You’ll receive emails from us every time we publish something new from Bio, as well as other new and interesting military aviation posts we think you’ll enjoy.

Want More Military Aviation Goodness?

Join us in our private Facebook group where you can enjoy the company of other likeminded military aviation fans, including a growing number of former & current military pilots, Radar Intercept Officers (RIO’s) and Weapon Systems Officers (WSOs).

Plus, get access to our videos and livestream content, all free of charge.

Click this link or the photo below to join.

8 Responses

Great article! Thx Bio.

/FlyBoy

Great article Bio! Thank you for sharing your experiences

Thanks Simon. I’ve let Bio know about your comment. Glad you enjoyed the article.

Thanks Simon. I was fortunate to experience many cool and amazing things, so I enjoy sharing them.

Thanks for your feedback Simon. I’ve passed it onto Bio for you.

Awesome reading, thank you! I’ve seen the more common ‘vapor cone’ or cloud countless times (and once that cost a Tomcat crew their wings unfortunately) but I’m also familiar with the less common transparent one that you describe, where it can only be seen by sort of diffracting the light going through it. Very cool stuff and you’re the first one that I’ve ever heard describe it from inside the cockpit.

Thanks for your comment Ken. When Bio sent me this article to publish, I didn’t actually realise there was a difference between the “vapes” and this, so he dug up that pic of the Hornet for me to demonstrate it.

I’ll pass your kind words onto him.

Seeing that was one of several times I wish I had my camera in the cockpit. But actually, I was focused on our mission and didn’t want the distraction. We did well so in the big picture it was probably best I didn’t have it.